When you pick up a prescription for a generic drug, you might think you’re just saving a few dollars. But behind that simple swap is a complex economic machine that’s saving billions - and sometimes, it’s not working the way it should. Cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t just a fancy term for budgeting. It’s the tool that tells us whether a $2 generic pill does just as much good as a $200 brand-name one - and whether we’re choosing the right one.

How generics change the game

Generic drugs aren’t knockoffs. They’re exact copies of brand-name medicines, approved by the FDA after proving they work the same way in the body. The big difference? Price. When the first generic hits the market, the brand-name drug’s price usually drops by nearly 40%. By the time six or more generics are competing, the price falls more than 95% below the original. That’s not inflation - that’s market discipline. In 2022, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they accounted for just 17% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition. Over the last decade, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion. That’s enough to cover the annual healthcare costs of every person in Texas and Florida combined. But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal. Some cost five, ten, even twenty times more than others that do the exact same thing. A 2022 study in JAMA Network Open looked at the top 1,000 most-prescribed generics. It found 45 of them were priced 15.6 times higher than cheaper alternatives in the same therapeutic class. That’s not a mistake. It’s a market failure.What cost-effectiveness analysis actually measures

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) answers one question: What are we getting for our money? It doesn’t just look at price. It compares cost to health outcomes - usually measured in QALYs, or quality-adjusted life years. One QALY equals one year of perfect health. If a drug extends life by two years but the patient spends half of that time in pain or disability, it might count as 1.5 QALYs. The key metric is the ICER - incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. It’s calculated by dividing the extra cost of one treatment by the extra health benefit it delivers. For example, if Drug A costs $10,000 and gives 1.2 QALYs, and Drug B costs $15,000 and gives 1.5 QALYs, the ICER is ($15,000 - $10,000) / (1.5 - 1.2) = $16,667 per QALY. That’s the price of each additional year of healthy life. In the U.S., many payers use a threshold of $50,000 to $150,000 per QALY to decide what to cover. In the UK, NICE uses £20,000-£30,000. If a generic drug’s ICER is below that, it’s considered cost-effective. Simple. Except it’s rarely that simple.Why most cost-effectiveness studies get it wrong

Here’s the dirty secret: 94% of published cost-effectiveness analyses don’t account for what happens next. They assume the brand-name drug will stay expensive forever. They ignore the fact that generics will come, prices will drop, and the whole calculation will change. A 2021 ISPOR conference paper showed that analysts routinely treat a $100 brand-name drug as if it’ll always cost $100 - even when its patent expires in six months. That makes generics look like a bad investment. But if you model in the price drop, the same generic becomes the most cost-effective option by far. This isn’t just a technical error. It’s a bias. Drug companies fund many of these studies. And when you assume the brand drug stays expensive, your analysis will naturally favor it. A 2000 review in Health Affairs found industry-funded studies were far more likely to report favorable results than independent ones. Even the pricing data used in these models is flawed. Analysts often use Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is known to be inflated. For generics, the real price is often 64% lower than AWP. For brand drugs, it’s 121% higher. If you use the wrong number, your whole analysis is off.

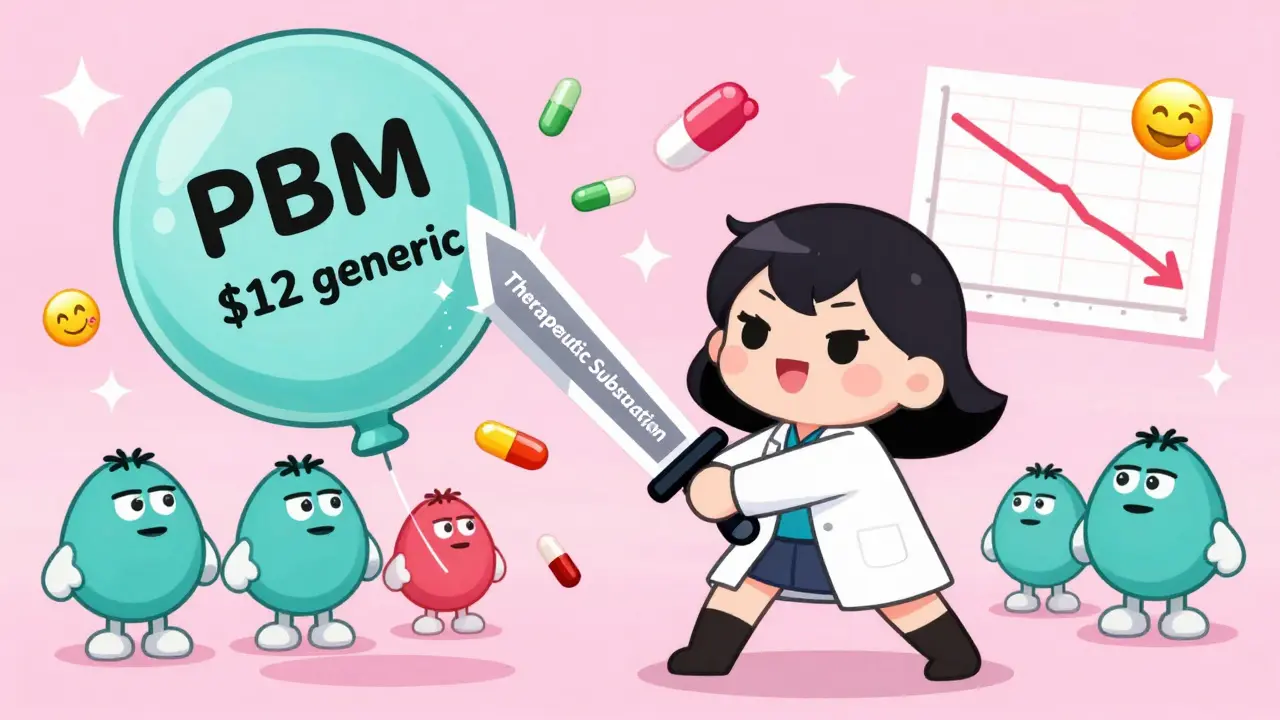

The hidden players: PBMs and spread pricing

You’d think that if a cheaper generic exists, doctors and insurers would switch. But they don’t always. Why? Because Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) - the middlemen between insurers and pharmacies - profit from the gap between what they pay pharmacies and what they charge insurers. That’s called “spread pricing.” Let’s say a generic pill costs $3 at the pharmacy. The PBM negotiates a $10 price from the manufacturer and charges the insurer $12. They pocket $2 per pill. But if the insurer switches to a $1 generic, the PBM’s spread shrinks to $1. So they keep the $10 version on the formulary - even though it’s five times more expensive and does the same thing. This isn’t theoretical. The JAMA study found that in many cases, the cheapest therapeutic alternative was being blocked not by clinical evidence, but by financial incentives built into the system. The result? Patients pay more. Insurers pay more. The system pays more.Therapeutic substitution: the overlooked savings opportunity

You don’t always have to switch to the same drug. Sometimes, switching to a different drug in the same class - a “therapeutic substitution” - saves even more. The JAMA study found that when doctors swapped a high-cost generic for a lower-cost alternative in the same therapeutic class, savings jumped to 88% in some cases. For example, two different statins for high cholesterol might both be generics. One costs $12 a month. The other costs $1.20. Both lower LDL cholesterol equally well. But most formularies still list the $12 version because it’s been on the list longer - or because the PBM gets a bigger cut. This isn’t about clinical superiority. It’s about inertia, pricing quirks, and hidden incentives. The NIH says therapeutic substitution is one of the “easiest-to-implement” savings opportunities in healthcare. Yet it’s rarely done.What needs to change

To fix this, we need three things:- Real-time pricing data - not outdated AWP, not manufacturer-listed prices. Actual pharmacy acquisition costs.

- Dynamic modeling - CEA models must forecast when generics will enter the market and how prices will fall. If a patent expires in 18 months, your analysis should reflect that.

- Transparency in PBM contracts - if PBMs are profiting from price spreads, we need to know. Some states now require PBM pricing disclosures. More should follow.

Where the U.S. stands vs. the rest of the world

In Europe, over 90% of health technology assessment agencies use formal CEA to decide which drugs to fund. In the U.S., only 35% of commercial insurers do. Medicare doesn’t use CEA at all - it’s legally barred from negotiating prices based on value. That’s changing. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act lets Medicare negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs starting in 2026. Those drugs? Many are still brand-name. But the next wave? Generics. And when those come up for review, the system will need to be ready. The lesson is clear: cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t just about saving money. It’s about saving lives - by making sure the right drug gets to the right patient at the right price.What is cost-effectiveness analysis in the context of generic drugs?

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) compares the cost of a generic drug to the health benefits it provides, usually measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). It helps decision-makers determine whether switching from a brand-name drug to a generic - or choosing one generic over another - delivers the best value for money. The key output is the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which shows how much extra cost is needed to gain one additional unit of health benefit.

Why do some generic drugs cost so much more than others?

Price differences among generics often come from market structure, not quality. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) may profit from higher prices through spread pricing, keeping expensive generics on formularies even when cheaper alternatives exist. Other reasons include lack of competition, complex formulations, or formulary inertia - where insurers stick with a drug simply because it’s always been there.

Can switching to a cheaper generic really save money?

Yes - dramatically. A 2022 study found that replacing high-cost generics with lower-cost therapeutic alternatives saved nearly 90% in spending. For example, one group of 45 overpriced generics cost $7.5 million annually; switching to cheaper alternatives would have cut that to just $873,711. Even within the same drug, switching manufacturers can save up to 30%.

Why do most cost-effectiveness studies ignore future generic prices?

Because many studies are outdated or funded by brand-name drug companies that benefit from assuming prices stay high. Analysts often use static pricing data, ignoring patent expiration timelines. This makes generics look less cost-effective than they are. The result? Decision-makers miss opportunities to save billions.

What’s the difference between therapeutic substitution and generic substitution?

Generic substitution means replacing a brand-name drug with the exact same active ingredient from a different manufacturer. Therapeutic substitution means switching to a different drug in the same class - like swapping one statin for another - that has the same clinical effect but costs less. Therapeutic substitution often saves more money, but it’s less common because prescribers and payers are hesitant to change the drug class.

Is cost-effectiveness analysis used in U.S. Medicare?

No - Medicare is legally prohibited from using cost-effectiveness analysis to set drug prices. This means it can’t refuse to cover a drug just because it’s not cost-effective. However, the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act now allows Medicare to negotiate prices for a limited number of high-cost drugs, which opens the door for future value-based decisions.

Alex Warden

January 2, 2026This whole generic drug thing is just socialism in a pill bottle. We got cheap meds because lazy Americans won't pay for quality. The FDA lets any factory in China slap a label on a powder and call it medicine. We're not saving money, we're just getting sick faster.