When you pick up a prescription, you might assume the pharmacist will always give you the cheapest version of your medicine. But that’s not true everywhere. In some states, pharmacists must swap your brand-name drug for a generic. In others, they can only do it if you say yes. These differences aren’t just paperwork-they directly affect how much you pay, whether you take your medicine as directed, and even how long you live.

What’s the Difference Between Mandatory and Permissive Substitution?

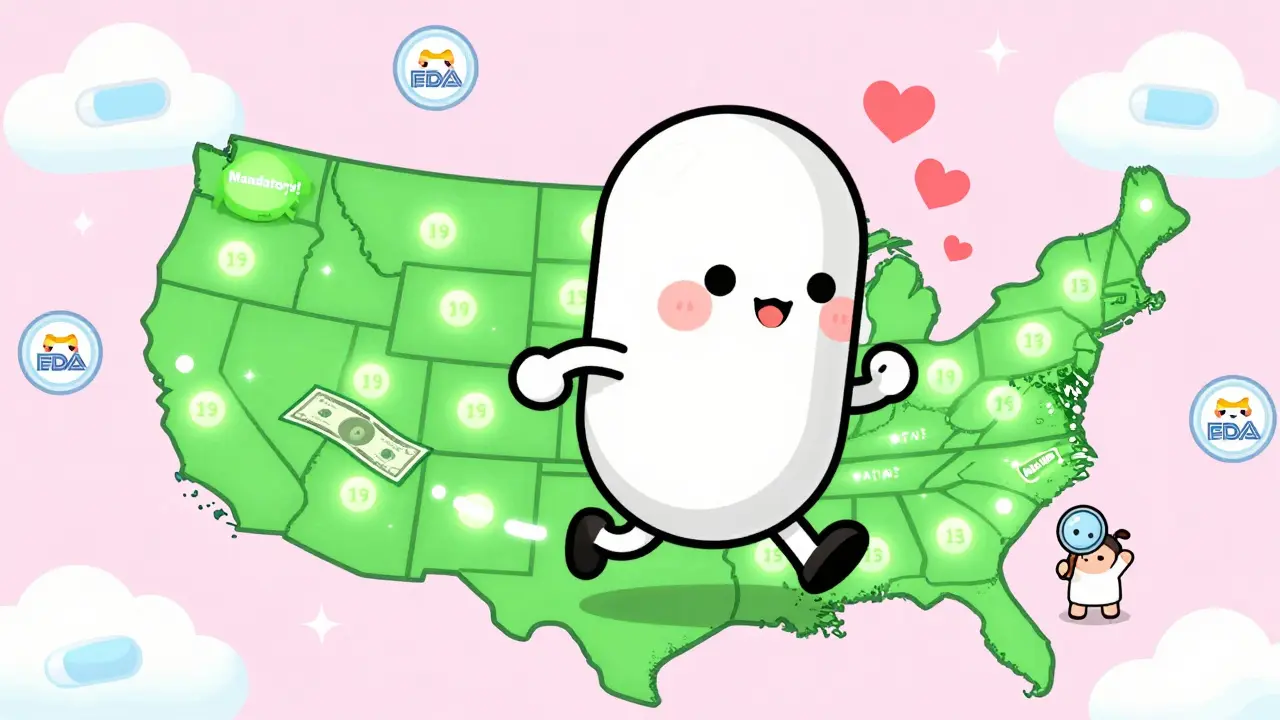

Mandatory substitution means the law forces pharmacists to give you the generic version of a drug-unless your doctor specifically says not to. Permissive substitution means pharmacists are allowed to swap the drug, but they don’t have to. They can choose to give you the brand name, even if the generic is cheaper and just as effective. This isn’t a federal rule. It’s decided by each state. The federal government lets the FDA approve generics as safe and effective, but it leaves the final call on who gets to swap them up to state legislatures. That’s why two people with the same prescription, living just across a state line, can have completely different experiences at the pharmacy. As of 2020, 19 states required pharmacists to substitute generics by default. That includes places like Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, and West Virginia. In those states, if your doctor doesn’t write "Dispense as Written" or "Brand Medically Necessary," the pharmacist is legally obligated to give you the generic. In the other 31 states and Washington, D.C., the decision is optional. The pharmacist might offer the generic, but they might not-and you might never know unless you ask.Why Does This Even Matter?

Generic drugs cost 80% to 85% less than brand-name versions. That’s not a small savings. For people on Medicaid or Medicare, or those paying out of pocket, that difference can mean choosing between medicine and groceries. A 2011 study tracked simvastatin-a common cholesterol drug-right after its patent expired. In states with mandatory substitution, 48.7% of prescriptions were filled with the generic version within six months. In permissive states? Only 30%. That’s nearly a 20-point gap. And it gets worse: in states that required patient consent before substitution, generic use dropped to just 32.1%. In states without consent requirements, it jumped to 98.1%. Why? Because asking for consent adds friction. Pharmacists don’t want to risk a patient saying no, especially if they’re in a hurry or don’t understand the difference. So they just give the brand name. That’s not because it’s better-it’s because the system makes it easier to avoid the swap.What Else Do These Laws Control?

It’s not just about whether substitution is required. States also control four other things:- Notification: Do you have to be told when a switch happens? 31 states and D.C. require pharmacists to give you a separate notice-not just rely on the label on the bottle.

- Consent: Do you have to sign or say yes? Seven states plus D.C. require explicit consent, meaning you have to actively agree before the swap.

- Liability: If something goes wrong after a generic is given, can you sue the pharmacist? 24 states don’t protect pharmacists from being held liable, which makes them more cautious.

- Prescriber restrictions: Can your doctor block substitution? Yes, in every state. But how they do it varies. Some states use special two-line prescription pads. Others require the doctor to write "Do Not Substitute" by hand. A few even require the doctor to explain why they’re blocking it.

These details matter. A pharmacist in a state with mandatory substitution but no consent requirement is far more likely to make the switch than one in a state with mandatory substitution but strict consent rules. The JAMA study found pharmacists in the latter group were nearly twice as likely to avoid substituting drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes-medicines like warfarin or lithium where even tiny changes in dosage can cause serious side effects.

How Do States Decide What Drugs Can Be Substituted?

Most states rely on the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists drugs approved as therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. If a generic is in the Orange Book, it’s considered safe to swap. But some states go further. A few use "positive formularies," meaning they list only the drugs pharmacists are allowed to substitute. Others use "negative formularies," listing the ones they can’t swap-like certain epilepsy or psychiatric drugs. Most, though, just follow the Orange Book and leave it at that. For biosimilars-expensive, complex drugs that mimic biologics like Humira or Enbrel-the rules get tighter. Forty-five states have stricter rules for biosimilars than for regular generics. Many require the doctor to be notified before substitution, or even to give explicit approval. That’s because biosimilars are more complicated to produce, and there’s still debate over whether switching between them and the original drug could cause immune reactions.What’s the Real Impact on Patients and Costs?

The bottom line? Mandatory substitution without patient consent leads to the highest generic use-and the biggest savings. The Congressional Budget Office estimated in 2011 that increasing generic use by just 1% would save Medicare Part D $160 million a year. Multiply that by the 18.7-point gap between mandatory and permissive states, and you’re talking about billions in potential savings annually. For patients, higher generic use means fewer skipped doses, fewer ER visits, and better long-term outcomes. People who can’t afford their meds often stop taking them. Generics remove that barrier. But if the system makes substitution hard, even when it’s safe, people pay more and suffer more. In states with permissive laws, brand-name manufacturers have an advantage. They can spend more on marketing, offer coupons, or train doctors to write "Dispense as Written" more often. That’s why you’ll see more brand-name ads in states where pharmacists can’t automatically swap.Why Are Some States Moving Toward Mandatory Substitution?

Between 2014 and 2020, the number of states requiring substitution jumped from 14 to 19. That’s not a coincidence. As drug prices keep rising, state governments are looking for ways to cut costs without sacrificing care. Health economists, like Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard, say the clearest path forward is to make substitution the default. "Optimizing state laws to facilitate generic drug substitution as the default option is an important lever to increase medication adherence and reduce excess drug spending," he said in the JAMA study. States that have made the shift report higher generic use, lower Medicaid spending, and no increase in adverse events. That’s the key: it’s not just cheaper-it’s just as safe.

What Should You Do as a Patient?

You don’t need to know every state law. But you should know your rights:- Always ask: "Is there a generic version?"

- Check your receipt or pharmacy label-some states require a notice if a substitution happened.

- If your doctor wrote "Dispense as Written," they’ve blocked substitution. That’s legal-but you can ask why.

- If you’re on a high-cost drug, ask if a generic or biosimilar is available. Don’t assume you’re getting the cheapest option.

- If you think a substitution caused a problem, report it to your pharmacist and doctor. Liability protections vary by state, so documentation matters.

Even in permissive states, pharmacists often want to help you save money. But they won’t act unless you give them the opening.

What’s Changing Now?

The trend is clear: more states are moving toward mandatory substitution. But as biologics and biosimilars become more common, lawmakers are adding layers of caution. Some states are testing new models-like requiring pharmacists to notify prescribers after substituting a biosimilar, or mandating electronic records of all substitutions. The goal isn’t to stop substitution. It’s to make it smarter. For small-molecule drugs, the evidence is overwhelming: mandatory substitution saves money and improves health. For biologics, the science is still catching up. So states are being careful. But one thing won’t change: if you’re paying for your meds, you deserve to know what you’re getting-and you should be able to get the best value without jumping through hoops.Can my pharmacist switch my brand-name drug without telling me?

In 19 states, pharmacists are required to substitute generics unless the doctor says not to, but they still must notify you separately-usually with a printed notice or label-unless your state has no notification rule. In 31 states and D.C., substitution is optional, so if the pharmacist doesn’t offer a generic, you might not know one exists. Always ask.

Do I have to give consent to get a generic drug?

Only in seven states and Washington, D.C. In those places, pharmacists must get your explicit approval-either verbal or written-before swapping your brand-name drug. In all other states, consent isn’t required, so the substitution can happen automatically if the law allows it.

Why do some doctors write "Do Not Substitute" on prescriptions?

Doctors use "Do Not Substitute" or "Dispense as Written" to block a generic swap. This is legal in every state. Sometimes it’s because the drug has a narrow therapeutic index-like seizure meds or blood thinners-where even small differences can be risky. Other times, it’s based on habit, lack of awareness about generics, or pressure from drug companies. You can always ask your doctor why they wrote it.

Are biosimilars treated the same as regular generics?

No. Forty-five states have stricter rules for biosimilars than for regular generics. Many require the doctor to be notified before substitution, or even to approve it in advance. That’s because biosimilars are more complex, and switching between them and the original drug can raise safety concerns. The rules are still evolving.

Can I be held liable if a generic drug causes side effects?

No, patients aren’t liable. But pharmacists in 24 states have no legal protection if something goes wrong after a substitution. That’s why some pharmacists avoid swapping drugs unless they’re forced to-or unless the patient insists. It’s not about safety-it’s about legal risk.

Nancy Kou

December 20, 2025This is the kind of systemic injustice that keeps people sick just so corporations can profit. Generics are just as safe, but the system is rigged to make you jump through hoops. It's not about health-it's about who controls the cash flow.